Secrets to sulphur success

Agronomists were asked to consider the impact of sulphur leaching in an informative session led by Dr Chris Guppy during Incitec Pivot Fertilisers’ recent Agronomy Community forums.

Agronomists were asked to consider the impact of sulphur leaching in an informative session led by Dr Chris Guppy during Incitec Pivot Fertilisers’ recent Agronomy Community forums.

Dr Guppy, Associate Professor in soil fertility at the University of New England, reminded agronomists of the mobility of soil sulphur.

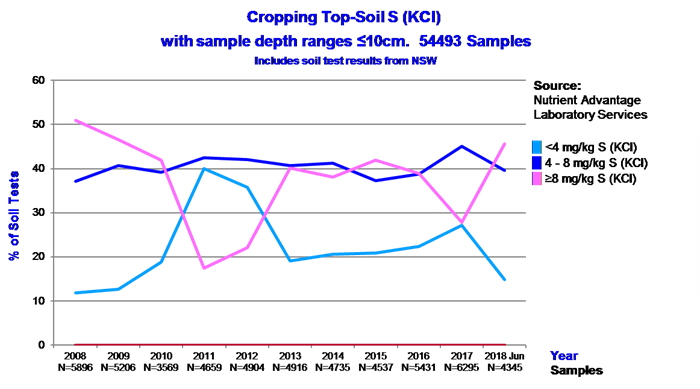

Using soil test data for New South Wales from the Nutrient Advantage® laboratory over the past 10 years, he showed clear links between topsoil sulphur levels from cropping soil tests and rainfall.

“If we look at 2011, we can see that rainfall leached the sulphate out of the topsoil of the cropping country, so you’ve got that dip in the trend line where the percentage of high sulphur results drops and the percentage of low sulphur results rises,” he explained.

“Compare that with the recent drought in New South Wales, and it looks quite clear that the laboratory is picking up the surface moisture conditions, which is the key driver of sulphur mobility in the landscape.

“Sulphur leaches. You can see it here across the whole of New South Wales.”

In cropping, Dr Guppy said there were only a few recorded responses to sulphur fertilisers in trials, because crops usually had access to enough sulphur at depth to buffer against any problems caused by low sulphur levels in the topsoil.

Incitec Pivot Fertilisers’ agronomist, Craig Farlow, agrees and suggests a better approach is to sample and test for sulphur in segments down to rooting depth.

“Segmenting soil samples between shallow and deep layers, as with nitrogen, can better define how much sulphur is in the profile and where it lies,” he said.

This was demonstrated in an Incitec Pivot Fertilisers’ canola nutrition trial near Sherwood in South Australia last season. Soil samples were taken at increments of 0-10 cm, 10-40 cm and 40-70 cm, showing low sulphur levels at the surface and large reserves at depth, but the reverse with nitrogen.

“This is typical of many soils and shows the value of segmented sampling,” he said.

The canola crop was quick to falter where there was a lack of applied nitrogen, but was able to utilise the subsoil sulphur to good effect.

“Knowing how much nitrogen and sulphur is in the profile and how readily accessible they will be at early and later growth stages allows better decisions around the right rate, timing and fertiliser source,” said Mr Farlow.

Dr Guppy said sulphur fertilisers were critical to the productivity of pasture systems and responses to sulphur in pasture trials were much more common.

He showed trial results from the New England comparing the clover yields achieved from a range of fertilisers.

Fertilisers with a higher available sulphur content, including single superphosphate and a Granulock® product outperformed MAP.

In his review of sulphur fertilisers, Dr Guppy suggested agronomists consider the form of sulphur in the fertiliser, not just the overall concentration.

While sulphate sulphur is immediately available to plants, he said the value of elemental sulphur was that it was slow release.

“How quickly it oxidises to sulphate sulphur depends on particle size and product structure,” he said.

“The smaller the size of the elemental sulphur particles, the more rapidly it releases.”

Dr Guppy said recent research had shown that the half-life of pure elemental sulphur (when about half of it is released under ideal conditions) was around 35 days, but when elemental sulphur is mixed into a multi-nutrient granular product, the half-life moved out to 140 days.

“The reason it takes longer is because we’ve got to wait for the nitrogen and phosphorus to dissolve and move away from the granule before the elemental sulphur can come into contact with the soil,” he explained.

Based on his review of currently available sulphur fertilisers, he said Granulock SS was a good product for agronomists to recommend.

Granulock SS contains 10% nitrogen, 17.5% phosphorus and 12% sulphur. This includes 4% sulphate sulphur and 8% ultra-fine elemental sulphur.

Dr Guppy suggested that with regular use, the elemental sulphur in Granulock SS would become available in a cycle that would supply a relatively constant amount of sulphur.

At the other extreme, he said some sources of sulphur bentonite pastilles could remain intact even after a decade on the ground, meaning that the sulphur stayed unavailable to plants.

He also suggested farmers and agronomists steer clear of any elemental sulphur coated fertilisers, as the friction and dust could prove explosive.